What You Measure Matters

The cattle industry talks a lot about data. But most of what’s measured—and taught—doesn’t translate to fertility, longevity, or profit. It looks good in a sale catalog. It fits a spreadsheet. But it falls apart in the pasture.

Meanwhile, fertility is in decline. Calf crops are shrinking. Inputs are rising. And producers are being told the problem is management.

We disagree.

The Data Says It All

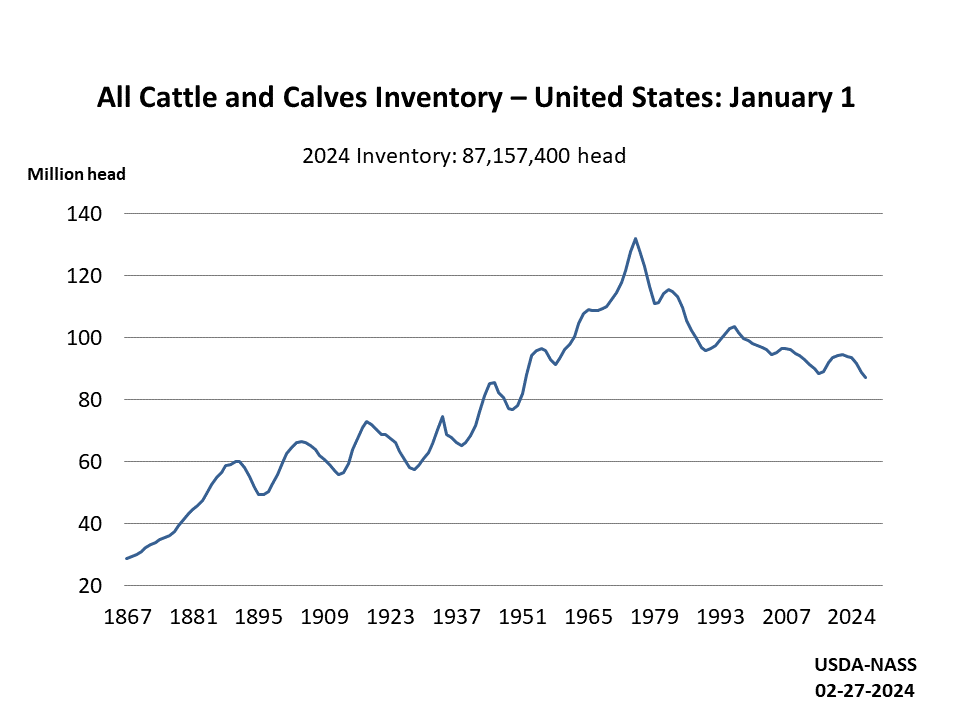

Cattle numbers in the U.S. are at their lowest in over 50 years. That's not because people aren’t trying—it’s because the model is broken.

A 90% calf crop is the breakeven point. Most international systems are nowhere close. If your herd isn’t averaging that or better, the genetics—not the management—might be the real issue.

Fertility Is Highly Heritable

The industry tells you fertility is lowly heritable. That’s not true. It’s just that most systems don’t measure the right indicators.

A 2021 study out of Australia showed that real fertility traits like age at puberty (AGECL) and postpartum anestrus interval (PPAI) have heritabilities of 56% and 42%, respectively. That’s highly heritable—and highly overlooked.

What’s measured matters. And most programs are measuring the wrong things.

Profit Per Acre > Profit Per Head

Rancher A.

50 Cows on 200 acres.

90% Calf Crop

45 calves to market

Average weight of 450 pounds.

20,250 pounds of live animals.

101.25 pounds per acre.

Rancher B.

40 Cows on 200 acres.

90% Calf Crop

36 calves to market

Average weight of 475 pounds.

17,100 pounds of live animals.

85.5 pounds per acre.

You don’t get paid by the pound of potential. You get paid by the pound of beef you ship—and how many acres it took to produce it. Rancher B’s calves weigh more. But Rancher A runs more cows per acre and weans more total pounds. That’s the difference between selection for individual performance vs. selection for system-wide efficiency.

It’s not about how big one calf is—it’s about how many pounds your land can produce.

How EPDs Don’t Tell The Whole Story

EPD’s of Profit Per Acre Bred Animal (Bull A)

EPD’s of Profit Per Head Bred Animal (Bull B)

Look at the difference. Animals bred for per-head profit often have high growth traits, high input requirements, and short productive lifespans. Animals bred for per-acre profit are more moderate, more fertile, and last longer.

But here’s the kicker: many EPD systems penalize balance. If a cow works well across the board, she often looks average on paper.We’re not interested in EPDs that punish function. We’re interested in cattle that breed back, stay sound, and make money in the real world.

Environment-Specific Selection

As seen in the EPDs above, these two bulls aren’t bred the same—and they shouldn’t be expected to perform the same.

Bull A is built for a grass-based, low-input system. Bull B was bred for high feed, rapid gain, and a different environment entirely. Both might be good—but only one fits your operation.

You can’t select cattle in one environment and expect them to thrive in another. Genetics are not one-size-fits-all.

In a feedlot scenario, progeny from Bull B will outgain those from Bull A. But in a grass-only environment, it’s the opposite—Bull A’s offspring will outperform Bull B’s.

That’s because cattle bred like Bull B have enormous daily requirements just to maintain condition. On pasture alone, they often struggle—unless the rancher turns to heavy feed supplementation, which is rarely profitable and often not even feasible in many parts of the world.

Cattle bred like Bull A, however, are built for grass. They thrive in low-input systems and maintain body condition without a feed truck. That ability to perform on forage is what allows them to stay in the herd longer, breed back consistently, and produce a calf every year.

EPDs also ignore a simple truth: males and females are biologically different, and they will perform differently—even when they share the exact same genetics.

Take a 15-month-old bull and his 15-month-old full-sister out of fertile, function-based bloodlines. Put them both into a performance test alongside generic cattle. That young bull might rank middle-of-the-road on growth—but his IMF score will likely suffer due to testosterone. Meanwhile, his sister may appear below average in frame and growth, but she’ll show a much higher IMF value.

Same genetics. Two very different outcomes. That’s not a flaw in the cattle—it’s a flaw in the model.

The Bos Sires Standard

This isn’t about ribbons. It’s not about spreadsheet cattle, either.

It’s about real-world performance—on grass, under pressure, and without excuses.

We measure what matters: fertility, adaptability, longevity, and pounds weaned per acre.

That’s what builds herds that last—and operations that don’t just survive but thrive.